Nuclear submarines, known as the "lonely assassins," usually operate far from the shore, sailing alone in the depths of the ocean for extended periods. The U.S. Navy's nuclear-powered submarines are designed to be deployed worldwide for several months at a time (currently, a mission cycle is about 70 days). If a serious injury occurs during a mission, it may take days for the injured to receive additional medical care. In 2005, the U.S. submarine USS San Francisco had a severe underwater collision, injuring 98 crew members. The following content is an introduction to the incident, with information sourced from publicly available online materials.

1. Introduction to the USS San Francisco Submarine

The USS San Francisco (SSN-711) is the 24th Los Angeles-class attack submarine, approximately 110 meters long, with a displacement of 6,900 tons and a submerged speed of 33 knots. The submarine can accommodate 129 officers and crew members and is equipped with an Independent Duty Corpsman (IDC). IDCs receive 12 months of clinical, laboratory, and radiology training at the Naval Undersea Medical Institute in Groton, Connecticut, as well as a 4-week intensive care training at the Yale-New Haven Medical Center in New Haven, Connecticut. During missions, the IDC and other formally trained crew members form an Emergency Medical Assistance Team (EMAT) responsible for basic medical treatment and care, including patient transport and intravenous catheter placement. Some EMAT members have received additional local training as emergency medical technicians. The onboard medical equipment includes basic laboratory equipment, an automated defibrillator, over 200 different medications, and other medical supplies. In most cases, the IDC can communicate with shore-based specialists via satellite.

2. The Rescue Process

On January 8, 2005, at 11:42 AM local time, the USS San Francisco (SSN-711) collided with an undersea mountain 360 nautical miles southeast of Guam. At the time of the collision, there were 138 people on board. The nearest port, Guam, was still two days' journey away.

Due to the lack of collision warning (typically issued during tactical maneuvers), the crew had no opportunity to prepare adequately. After the collision, the submarine quickly surfaced. The high-speed impact resulted in 98 injuries, including nine severe fractures (three upper limb fractures, two cervical fractures, two rib fractures, and one basilar skull fracture). There were two critically injured, 22 requiring immediate treatment, 32 who could wait for treatment, and most others sustained minor injuries. About 10% of the crew were uninjured, mostly because they were in confined spaces like bathrooms or bunks at the time (highlighting the importance of seat belts while driving).

Emergency Treatment Onboard

Due to the limited space in the submarine's medical quarters and the large number of injured, the main rescue operations were conducted in the crew's mess hall. This approach was later endorsed in the incident investigation report.

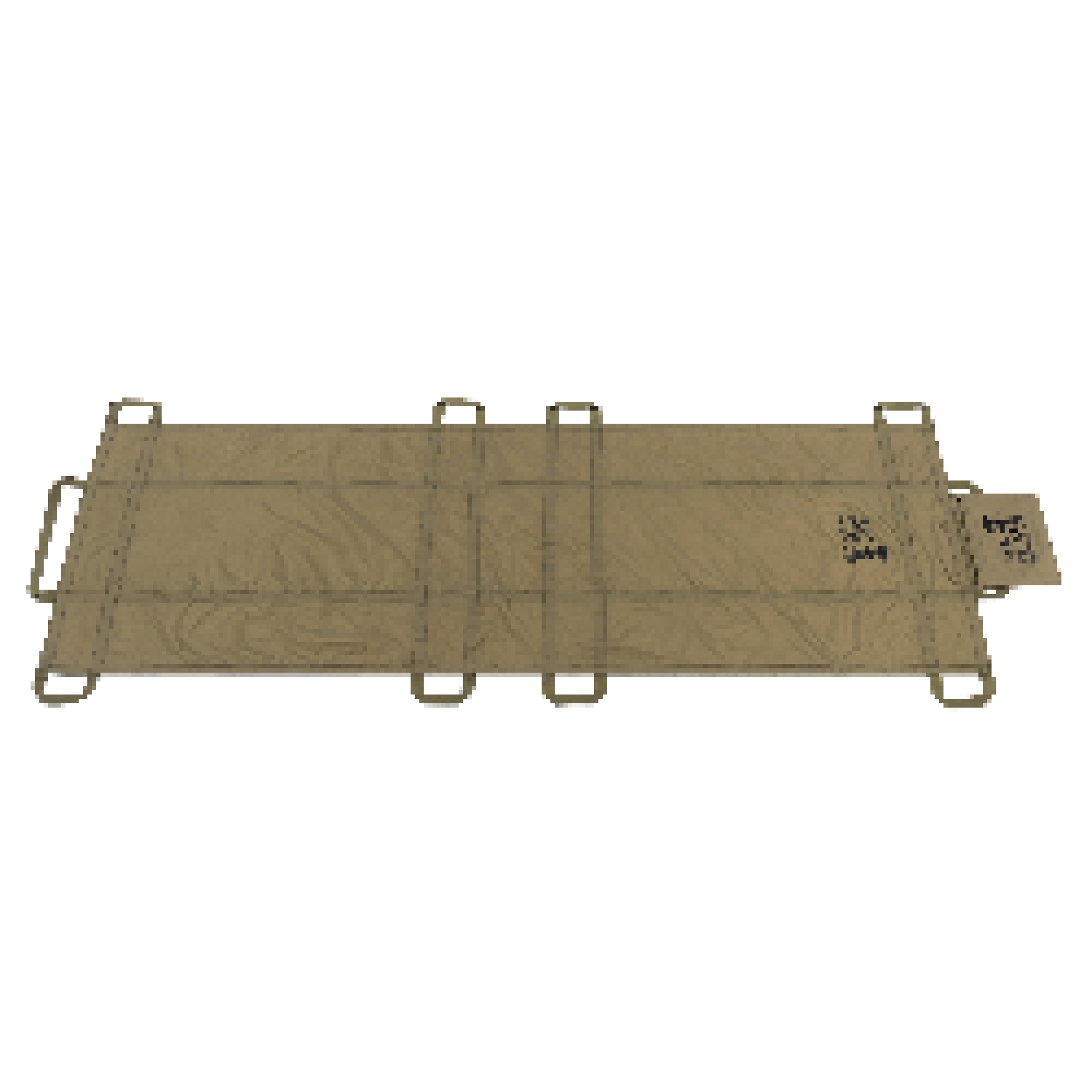

One injured person was thrown 20 feet during the collision, resulting in a fatal closed head injury. The IDC found him based on reports from other personnel, discovered he still had weak spontaneous breathing, and transported him to the mess hall using a Reeves stretcher. Initial vital signs in the mess hall were blood pressure of 190/74 mmHg, heart rate of 74 bpm, and respiration of 25 breaths per minute, with a vomiting response. Due to facial injuries, an airway could not be established through the nasal or oral route, and the IDC had not been trained in cricothyrotomy. Therefore, an oxygen mask was used to administer oxygen, and a urinary catheter was inserted. Under remote consultation with experts at Okinawa Hospital, the IDC administered mannitol to reduce brain swelling, repeatedly suctioned vomit to keep the airway clear, used morphine to lower heart and respiratory rates, and continuously monitored blood oxygen saturation. Despite the extensive efforts, the severe injuries were ultimately fatal.

Meanwhile, the IDC triaged other injured crew members, checked the airway, breathing, and circulation of another spinal fracture patient, and administered IV fluids and catheterization. The other EMAT members mainly cleaned wounds and assisted with minor tasks. The main assistance came from two uninjured crew members with some medical training—one trained as an EMT and an officer who had served as a corpsman but was not part of the core team.

Within 8-10 hours of the incident, all other injured personnel were treated, including suturing lacerations. Six oxygen bottles were exhausted, so the IDC had to use oxygen from the submarine's oxygen pipeline, which is now a standard practice, requiring familiarity with the submarine's oxygen pipeline and valves. Each submarine is now required to have four resuscitators (BVMs).

External Assistance

After surfacing, the submarine reported the situation to the Pacific Submarine Command. The command center considered deploying rescue personnel by air but opted for surface vessel support due to preparation constraints. The first to arrive was the Coast Guard cutter Galveston Island, reaching the incident site at 4:30 AM local time on January 9 (about 18 hours after the incident). Due to poor sea conditions and the low freeboard of the submarine, transferring a physician and IDC via small boat was deemed unsafe and abandoned.

Another rescue vessel was the Military Sealift Command's prepositioning ship USNS Stockham, which carried a rescue team and established a resuscitation surgical unit on board. Three rescue personnel and equipment were transferred to the submarine by helicopter. Throughout the rescue, the submarine maintained satellite communication with the Pacific Fleet Submarine Command Center in Hawaii, with guidance from neurosurgery experts at Okinawa Naval Hospital.

Patient Transport

SEAL medics performed a cricothyrotomy on the most severely injured head trauma patient and attempted to transfer him via the sail compartment, but the first attempt failed due to tube displacement. After securing the tube, another attempt failed, and the patient died after further resuscitation efforts.

The second severely injured patient could not be transported due to the sail compartment size. Medical personnel focused on further treatment of other injured crew, including correcting bandages and splints, and transmitted injury status to Guam Naval Hospital.

Subsequent investigation revealed that the sail compartment size was too small for the Reeves stretcher, causing head and facial compression. This led to testing on 12 Los Angeles-class submarines, finding five with sail compartments that could not accommodate the stretcher. Lack of pre-deployment training on the San Francisco led to this oversight.

Return to Port for Treatment

On January 10, after more than 30 hours of sailing, the submarine returned to Guam's Apra Harbor. Twenty-nine injured crew members were sent to Guam Naval Hospital for further examination and treatment, with three hospitalized for fractures. A psychological support team also provided immediate help to those in need.

Three months after the accident, 85% of the crew were in good health, with most unfit for return to duty due to psychological issues. Physical injuries were fully recovered, but two crew members were disqualified for psychological reasons.

Discussion

After returning to Guam, detailed evaluations of the medical rescue process led to improvements in emergency preparedness and disaster response for the entire U.S. submarine force.

IDC Training in Telemedicine

Uninterrupted medical communication and information transfer are crucial for remote operations. Enhanced training at the Naval Undersea Medical Institute now includes secure satellite communication and other methods for effective emergency response. An updated comprehensive medical guide for submarine command centers ensures accurate communication protocols.

Widespread First Aid Knowledge

The accident highlighted the importance of having medically trained personnel onboard. Subsequent policy changes require a minimum of six EMT-trained personnel per submarine, in addition to the IDC. EMT volunteers are selected from young sailors interested in medical or emergency response fields, with extensive training provided.

Follow-up for Injured Personnel

Detailed follow-up was conducted for all injured personnel from the collision. Patients experiencing chronic intermittent musculoskeletal pain are often unsuitable for submarine duties. Living spaces on submarines impose physical stress on the human body. Sleeping accommodations consist of independent bunk beds, stacked three high, with additional space constraints in work and living areas. Close monitoring of physical injuries ensured appropriate and timely recovery, resulting in all but two physically injured patients returning to their posts after three months.

Despite a proactive and effective program to identify and treat collision-related psychological health conditions, psychological disorders were the primary reason for crew members being unable to return to duty three months later. Previously published reports have acknowledged the ongoing development of post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health issues. Guam Naval Hospital allocated all their resources to survivors, arranging for a school psychologist and a certified social worker from the U.S. Navy Fleet and Family Service Center to provide psychological support for their spouses and families.

Within the initial three months following the collision, 17 submarine crew members required ongoing psychological therapy to cope with conditions potentially affecting their ability to perform submarine duties. There was no correlation between the severity of injuries sustained during the collision and the development of psychological conditions. Despite efforts to retain all submarine personnel in their current roles, only 2 out of 17 patients with psychological illnesses returned to submarine duty three months later.

The higher incidence of psychological casualties post-collision may partly be attributed to strict psychological standards for submarine crew members. However, a similar rate of psychological illness occurred after the 1975 collision at sea involving the U.S.S. BELKNAP, a guided missile cruiser, which resulted in 7 fatalities. Among the surviving 329 men, 18 previously without medical history required specialized psychiatric hospitalization over the next three years, with 13 hospitalized for neurology-related conditions. Within the first three months after this incident, 17 submarine crew members required subsequent psychological therapy. Despite medical efforts to facilitate the return of all submarine personnel through treatment, only 2 out of 17 individuals with mental health issues returned to submarine duty three months later.